The Greenwich Meridian

…where east meets west

The Millennium

The Greenwich Meridian and the Millennium

The Greenwich Meridian and the Millennium

Mention the millennium, and most people in the UK will think of the saga of the Millennium Dome. Few will recall Lord Tanlaw rising in the House of Lords in March 1998 to ask Her Majesty’s Government for their response to a claim being made, that the third millennium was ‘to be celebrated at Greenwich on the wrong meridian with the wrong time-scale and in the wrong year of the second millennium’.

The 1999 versus 2000 argument

In our system of counting years, there is no year zero. The year run goes straight from 1 BC (BCE) to 1 AD (CE). Because there is no year zero, an interval of 100 years only elapsed at the end of the year 100 AD. Likewise, 2,000 years only elapsed at midnight on 31 December 2000. Despite this, the World at large chose to celebrate the start of the third millennium not at the end of the year 2000, but at its start. That they did this was nothing new. The controversy had previously been aired in The Times both in 1899 and one hundred years earlier in 1799 when the paper stated:

We have uniformly rejected all letters and declined all discussion upon the question of when the present century ends? as it is one of the most absurd that can engage the public attention, and we are astonished to find it has been the subject of so much dispute, since it appears to be perfectly plain. The present century will not terminate till Jan. 1, 1801, unless it can be made out that 99 are 100 ... It is a silly, childish discussion, and only exposes the want of brains of those who maintain a contrary opinion to that we have stated... .

The same arguments were aired once again at the start of 2010, which many declared as the beginning of a new decade.

The moving Date Line

An area of speculation and extensive press coverage revolved around which point on land would see the first light of the new millennium. Things got very heated, when on 23 December 1994 the Republic of Kiribati, a group of Islands, divided by the International Date Line, announced that from 1 January 1995 it was uniting itself by pushing the Date Line eastwards. The government then changed the name of Caroline, the easternmost of its islands to Millennium Island and attempted to cash in by staking its claim for first light. In the event the claim was wrong.

Whilst the Kiribati controversy grabbed the headlines, other controversies were subtler and went largely unnoticed, particularly those which arose as a result of the niceties surrounding the meaning and use of Universal Time, which had been adopted at the start of the 20th century.

The millennium starts here ... or does it?

The millennium starts here ... or does it?

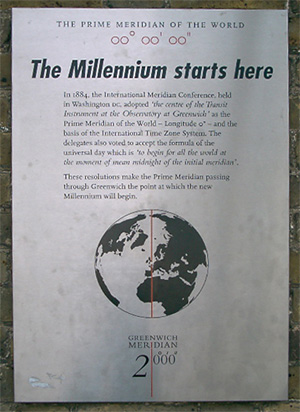

The seeds for confusion were sown at the International Meridian conference of 1884, when it was proposed not only that the Greenwich Meridian should be adopted as the Prime Meridian of the World, but also that there should be a ‘universal day for all purposes for which it may be convenient, and which shall not interfere with the use of local or other standard time …’. This universal day would ‘begin for all the world at the moment of mean midnight of the initial meridian, coinciding with the beginning of the civil day and date of that meridian’.

The key word here is ‘convenient’. For in effect, two widely different time systems are in operation, a local time and a universal time. Did the millennium begin at local midnight, in the time zone defined by the local jurisdiction or did it begin at midnight on the Meridian of Greenwich as the sign, outside the Royal Observatory, (which was rather more economical with the truth), had claimed? The pragmatic answer would be that it began at both. In reality though, this was not quite the case.

Our slowing Earth

Little by little, the Earth is slowing down – not at a steady rate, but at a rate that varies over time. So small is the change, that it remained undetected until the 20th century. Once detected though, it presented scientists with a problem. Like length and mass, time is one of the fundamental quantities and it is important that the units in which it is measured stay constant in value from one day to the next. With an Earth whose speed was changing, time itself was going to be a bit of a variable quantity. The development of the atomic clock, gave scientists the potential for a new time scale steadier than the Earth itself. In 1967, following much discussion and after years of careful measurements, International Atomic Time (TAI) was introduced and the second redefined. No longer was it formally to be 1/86,400 of a mean solar day, but ‘the duration of 9,192,631,770 periods of the radiation corresponding to the transition between the two hyperfine levels of the ground state of the caesium 133 atom’. The new definition although sounding complicated, assigned the second the same length that it had had on average during the year 1900 – the same length in fact that it had been assigned before the new definition came into effect.

With the Earth gradually slowing, but the timescale not slowing with it, the position of the Sun in the sky was set to get more and more out of step with the time it represented. The idea of 12 noon gradually shifting into the morning and then into the night was not something that most people wanted to contemplate – even if it was going to take tens of thousands of years to become significant.

The introduction of UTC

The problem was solved in 1972, with the introduction of an adjusted atomic time scale, Coordinated Universal Time (UTC). The rotation of the Earth is monitored by various organisations around the world, the data being coordinated by the International Earth Rotation Service (IERS) in Paris. Every now and again, (historically at the end of either June or December), an extra second known as a leap second, is introduced to keep UTC within 0.9 seconds of GMT. Although UTC has no legal status in the UK, it is this rather than GMT which is used in practice, as Lord Tanlaw made clear during the second reading of the Coordinated Universal Time Bill in the House of Lords on 11 June 1997. He also pointed out for those who were listening, that: ‘It is quite impossible ...to set a watch or clock to Greenwich Mean Time’ and ‘that when Big Ben ... strikes in the new millennium it will be UTC time …’. He went on to say how he hoped that the time displayed at the Millennium Dome, would be described correctly as UTC and not as GMT, ‘as is the case today outside the Maritime Museum at Greenwich.’ His rebuke, fell on deaf ears.

The countdown clocks

The countdown clocks

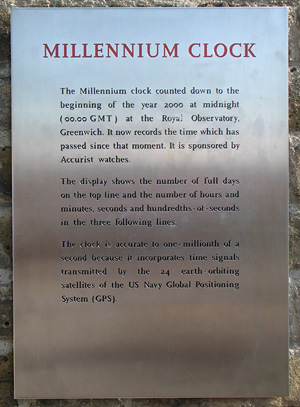

In April 1997, a countdown clock sponsored by Accurist was set running on the Line at the Royal Observatory. Like others around the World, it counted down the days, hours, minutes and seconds until the start of the year 2000. It is now counting upwards as the picture shows.

Although the sign displayed alongside it at the Observatory implies otherwise, it calculated the time left to the start of the millennium not in terms of GMT, but in terms of UTC as derived from the time signals it received from the GPS satellites.

When the 1000-day countdown began, the approach taken by the owners of the various countdown clocks was decidedly uncoordinated. Whilst most strived to estimate the number of leap seconds that would need to be allowed for, the National Maritime Museum (NMM) as custodians of the Royal Observatory decided that its countdown clock would not take leap seconds into account until they were actually inserted, at which point, the clock would effectively pause for a second. Inevitably, different authorities did not agree in their estimates of how many leap seconds would be added. So, when they started, the various countdown clocks differed from one another by one, two, or three seconds. Fortunately for the NMM, no leap second was added at the end of 1999. Imagine the embarrassment if under the full spotlight of the World’s media, the clock had counted down to zero, but with a second still to go before the start of the year 2000 (UTC).

When the 1000-day countdown began, the approach taken by the owners of the various countdown clocks was decidedly uncoordinated. Whilst most strived to estimate the number of leap seconds that would need to be allowed for, the National Maritime Museum (NMM) as custodians of the Royal Observatory decided that its countdown clock would not take leap seconds into account until they were actually inserted, at which point, the clock would effectively pause for a second. Inevitably, different authorities did not agree in their estimates of how many leap seconds would be added. So, when they started, the various countdown clocks differed from one another by one, two, or three seconds. Fortunately for the NMM, no leap second was added at the end of 1999. Imagine the embarrassment if under the full spotlight of the World’s media, the clock had counted down to zero, but with a second still to go before the start of the year 2000 (UTC).

Forward or backward looking?

One reason why the Millennium Dome was sited in Greenwich is that the Meridian runs though the site. Quite correctly, the various authorities turned to the NMM as custodians of the Airy Transit Circle for an official take on the Meridian. Some have argued, most notably Tom Standage in The Daily Telegraph (on 9 September 1997), that the NMM took a rather narrow approach to the matter. Standage argued that in a forward looking world, the position of the WGS84 Meridian should be given precedence over the Airy and be the one that was marked at the Dome. While not denying the existence of the WGS84 Meridian, the NMM repeatedly played down its significance. Although both meridians pass though the site of the Dome, only the Airy Meridian passes though the site of the Observatory. And it is to the Observatory that visitors come from all around the World in order to stand astride the Line. It is brand recognition like this that drives sponsorship and licensing deals. But those, who believed that the place to be at midnight UTC was on the WGS84 or the closely aligned International Reference Meridian, were also mistaken. As we have already seen, time has been decoupled from the spinning Earth. There is no link between UTC and any fixed point or line on the Earth, or indeed in the space above it, nor has there ever been.

A moving meridian

But if as the NMM claimed, the millennium was going to start at midnight GMT on the Greenwich Meridian, how, was anybody supposed to know when this moment had arrived since all the clocks showed UTC? Since the discrepancy between UTC and GMT was always going to be less than 0.9 seconds, this might sound rather nitpicking, especially as in the UK, the words UTC and GMT are often used interchangeably – particularly by the BBC and Her Majesty’s Government. But time and location are critical here. Each 0.1 seconds of time represents a distance on the ground of a little over 28 metres at the latitude of Greenwich. Were such a thing as a UTC meridian to exist, its distance at Greenwich from the Airy Meridian would vary continuously by up to 250 metres in either direction.

Too late? ... or too far west?

The uncertainties associated with predicting the Earth’s future rotation rate are not dissimilar to those associated with weather forecasting – the predictions tend to be reliable in the short term only. Only after the event, is it possible to determine (rather than estimate) the difference between GMT and UTC at any particular moment in time. At the end of 1999, this difference was decreasing by about a thousandth of a second a day – an amount that would have caused the hypothetical UTC meridian to move towards the Airy Meridian at a rate of roughly one foot a day. So did the people of Britain mark the start of the millennium at midnight GMT? There is only one answer. They most certainly did not. They marked it at midnight UTC. At the start of 1 January 2000, GMT was running 0.355499 seconds ahead of UTC. So in practice, depending on how you look at it: either the celebrations started on the Airy Meridian as the NMM claimed they should, but roughly a third of a second too late, or they started at midnight, but on a hypothetical meridian that at that moment was roughly 100 metres to its west – a line incidentally that passes through neither the curtilage of the Observatory or of the Dome.

The Meridian and the Dome

The Meridian and the Dome

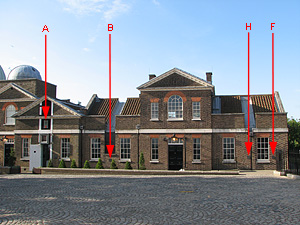

The people at the Dome were un-persuaded by Standage’s arguments and pressed ahead, with creating the Meridian Quarter containing extensions of the four meridians that were (until March 2010) marked as shown, on the external wall of the Meridian Building at the Royal Observatory.

The observant visitor to the Observatory will note that the marks on the wall of the Meridian Building do not all line up with the marks on the floor inside. They might enquire why the so-called Halley Meridian (H) is marked by the quadrant wall (and on the wrong side at that) rather than where it should be at the historic site of his transit instrument. They might ponder too, if John Flamsteed would have agreed with where his so-called meridian (F) is marked. And should this enquiring visitor make his or her way down to the Dome, they would probably not be surprised to discover that the four lines there are all marked too far to the west.

The phoenix rises

Although the Dome is the best known of the Millennium Projects to have actually been sited on the Greenwich Meridian, it was by no means the only one. Two other high budget projects were the Millennium Tree Line and a public sundial in Greenwich Park. Like the Dome, neither can be regarded as having been successful. But all is not doom and gloom, for although the Millennium Dome is widely remembered as a financial disaster, it is now said to be the most successful entertainment venue in the World.

Marking the Line

At the time of the millennium, beacons and fireworks were lit and many new markings of the Line occurred. The London Borough of Waltham Forest and the Sussex town of East Grinstead for example went overboard, marking the Meridian on virtually every street it crossed. There was a departure too – for the first time in the UK the WGS84 meridian was marked. Of the two such markings that are known, one was positioned by a pilot and the other by a naval man. Tanlaw and Standage would no doubt have been delighted.

Links:

Tanlaw and Standage

The wrong meridian with the wrong time-scale and in the wrong year – Lord Tanlaw’s question to the HouseCo-ordinated Universal Time Bill, second reading

Greenwich Mean Time and Trade Descriptions – a question from Lord Tanlaw

Tom Standage – An online article about the Meridian and the Dome

The counting of years

The 21st century and the third millenniumThe first decade of the twenty-first century

First sunrise of the new millennium

From the United States Naval ObservatoryA more lighthearted viewpoint from Grant Hutchison

From the International Herald Tribune

Coordinated Universal Time (UTC)

From NPL, the UK’s official timekeeperFrom the United States Naval Observatory

From Wikipedia

International Earth Rotation Service

Difference between UT and UTC at the time of the millenniumLeap seconds

From NPL, the UK’s official timekeeperLeap second notification bulletins